Every year at the start of winter, we take a glance into the rear-view mirror.

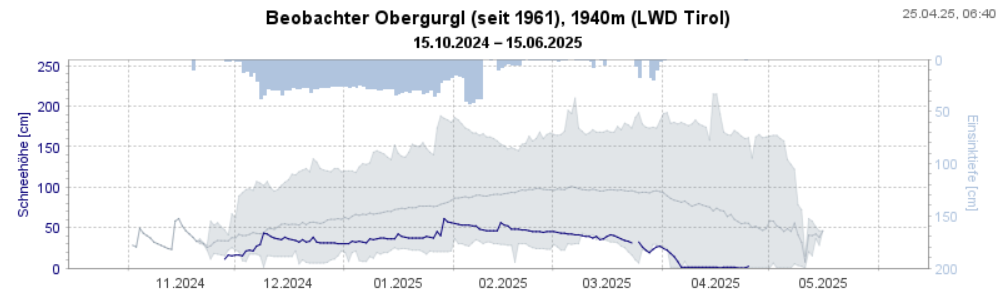

- Season 2024/2025 was one of the 10 driest winters since the beginning of measurements in 1858 (mid-value ~ 28% precipitation deficit in Tirol).

- Autumnal onset of winter in mid-September led to the first avalanche death of the season.

- White Christmas from the summits to the valleys – immense amounts of snow atop a faceted snowpack led to high avalanche activity.

- Recurring persistent weak layers in December and January due to snowfall at the end of each month.

- January-mid March, very little precipitation, mostly favorable avalanche conditions – but with little snow. Danger of stone contact persisted throughout the winter.

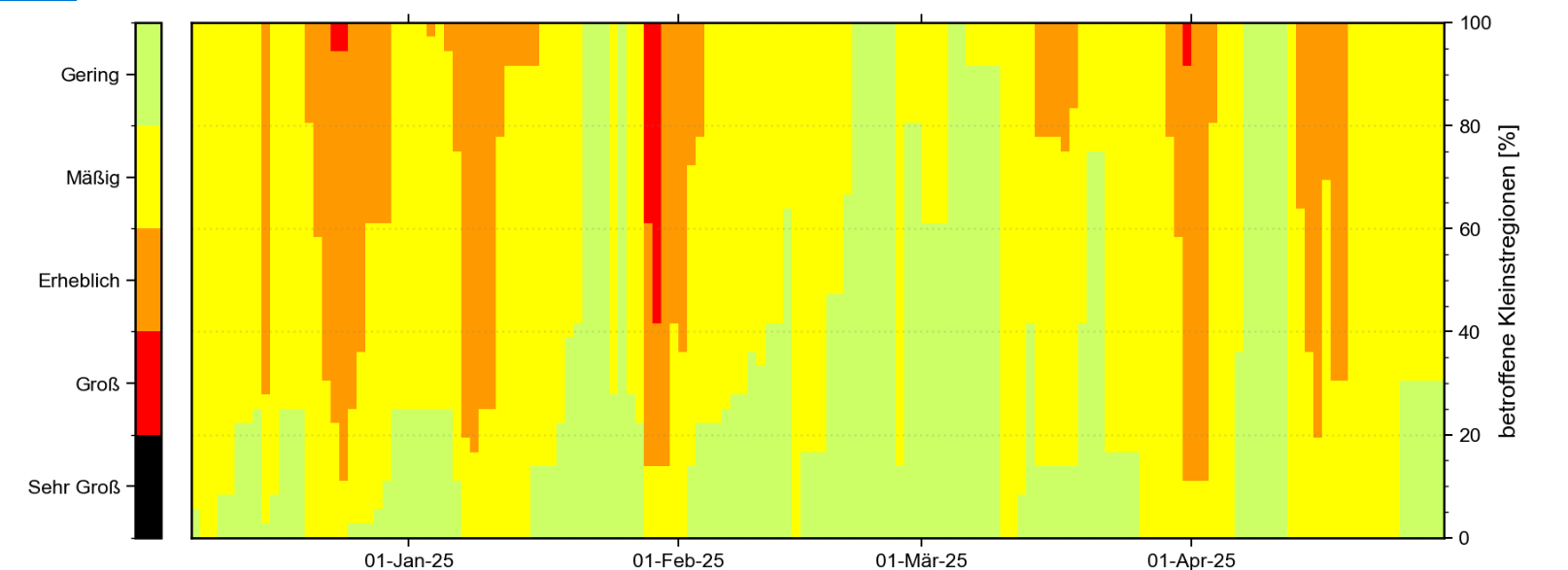

- High avalanche danger (danger level 4) on only 5 days – a situation with very threatening avalanche danger

Mid-September – powerful burst of winter, high glacier activity

September had heavy precipitation throughout Austria, in western regions more than at any time in measurement history. At mid-month in the mountains, winter arrived early with locally up to 150cm of fresh fallen snow atop the warm ground. This led to heightened gliding snow and loose-snow avalanche activity.

“The winter, despite isolated snowfall, remained unusually dry: Tirol had one of the seasons with the least precipitation in the last 160 years – high pressure fronts dominated for weeks on end, left Tirol waiting for snowfall in many places.”

Michael WINKLER

Glide-snow avalanches require steep terrain, smooth ground and a moist-to-wet ground-level snow layer as prerequisites. Through the film of water at ground level, friction decreases, which raises the likelihood of a gliding snow release. The heavy snowfall in mid-September favored these prerequisites: lots of fresh snow persisted on the still warm ground, long grass reduced the rawness of the terrain. The high gliding snow activity which resulted in Tirol brought about the first fatal casualty in the new season. A group of hikers was taken by surprise by a glide-snow avalanche while descending from Binsalm in the Karwendel and a life was lost.

Also subsequent to the heavy snowfall, there was another incident as a consequence of a naturally triggered glide-snow avalanche on the Bärenkopf in the Eastern Karwendel at 1991m. Two persons were caught in the avalanche, swept along for 10-15 metres and partially buried in snow. They escaped without injuries. What is interesting: this was the selfsame slope where on 09 April 2024, in other words nearly at the end of the previous season, where a group of hikers was caught by a glide-snow avalanche. Two persons were swept along, one person was dug out, but was dead. Since the process of gliding snow is so dependent on the type of terrain and the structure of the ground, glide-snow avalanches occur repeatedly in the very same places. Thus, in times of high gliding snow activity, such zones should be consciously avoided in order to reduce the risks.

Winter was just like autumn: mild, sunny, with little precipitation

Following the early intense onset of winter in mid-September, the remainder of autumn was extremely dry. October and November were mild, with numerous periods of fine weather. The snow that had fallen melted swiftly, so that by the start of December there was a cohesive, area-wide snowpack only on very high, shady slopes.

At the longstanding observation stations there were significantly reduced snow depths, sometimes just above the minimum. The situation on sunny slopes was striking: for long periods there was no snow on the ground, a condition which hardly changed throughout the winter. A plus of 15% of sunny hours, compared to the long-term average, as well as mild temperatures throughout the winter generated a season with little snow, particularly on sunny slopes. The generally low snow depths also led to increased danger of injuries from rocks, a risk which persisted throughout the winter.

All in all, winter 2024/25 was quite mild – with average deviencies of +1.4° and very little precipitation. In Tirol the deficit lay at about 28%. For all of Austria, the winter of 2024/25 numbers among the driest winters since the start of measurement in 1858. “There were frequent high-pressure fronts this winter, which repelled the low-pressure fronts in the north and south to detour,” reports Alexander Orlik from GeoSphere Austria. As a median value (from 1991 to 2020) there are about 18 days with snow on the ground in Innsbruck, but in January 2025 there were only six. Above 1000m altitude, the amounts of fresh fallen snow lay between 10 and 70% below the long-term median values. A new record was made in hours of sunshine: in the mountains an increase of 40-50% in hours of sunshine was recorded.

The mild temperatures had another consequence: during nearly all the winter months, there was rainfall up to and just over 2000m, a phenomenon often observed in recent years. Below the treeline, as a result, the snow depths remained well below average all season long.

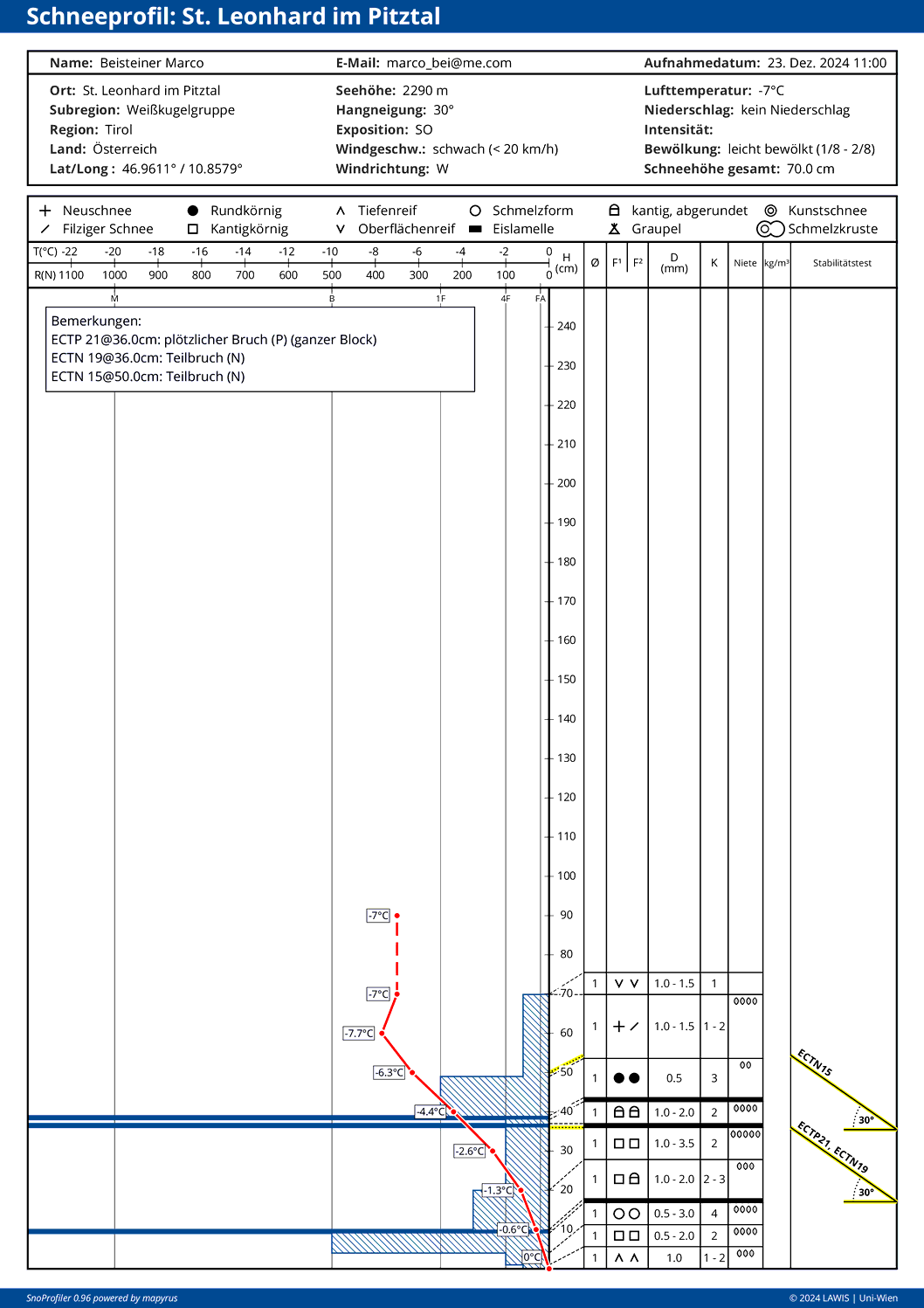

Early winter: weak layers = breeding ground for persistent weak layer problem

Following the mild and dry months of autumn, significant snowfall occurred on 5 December. This date marked the start of the daily Avalanche Bulletins. Due to the still low snow depths and a snowpack which was often not cohesive, area-wide, touring possibilities were very limited. Also the reports of observers from open terrain were sparse.

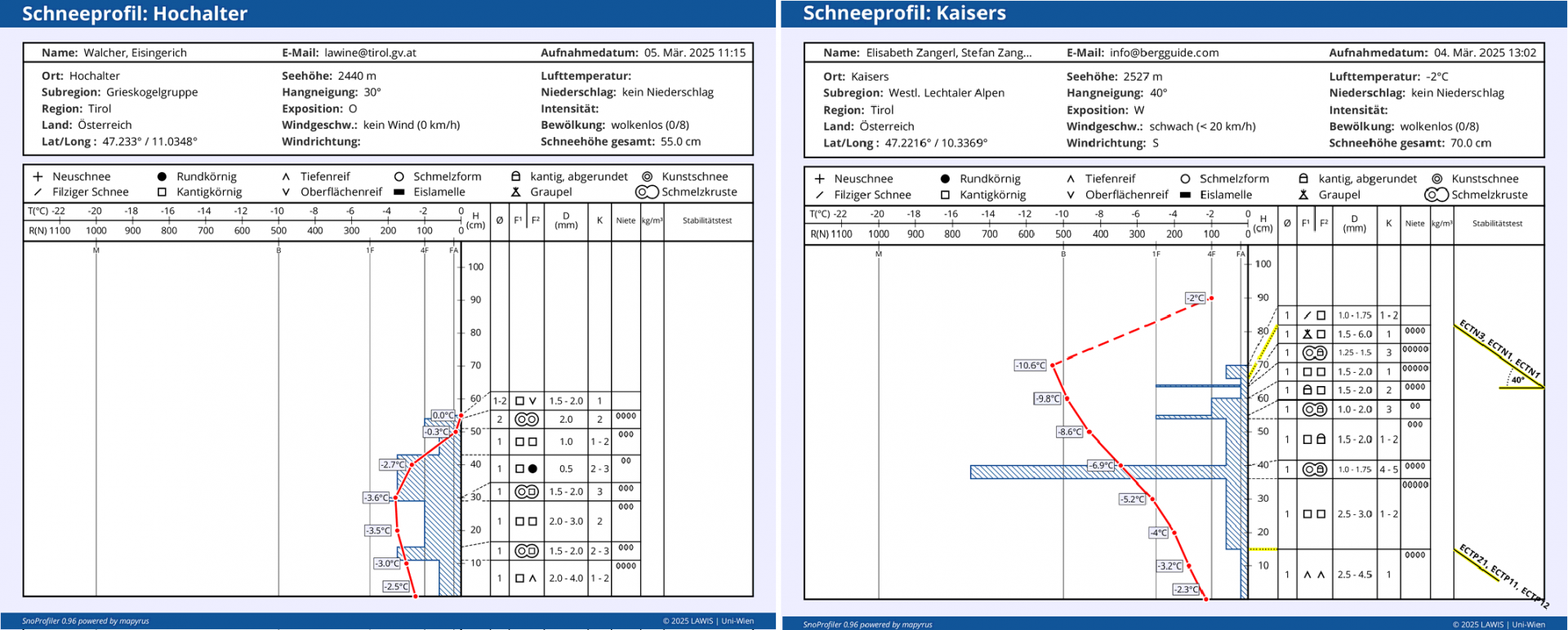

Little snow, dry weather at the start of winter furthers expansive transformation of snow crystals. In this process, faceted crystals form at the snow base – a persistent weak layer which is a central problem. For a slab to trigger, not only a weak layer is required, but also a bonded slab on top of it. This was evident only in some places in mid-December, namely, where the wind had deposited snowdrift accumulations on top of the ground-level weak layer. Precisely this constellation was the cause of the few avalanches which triggered during this period.

Wintery-white Christmas and the first avalanche cycle

“White Christmas from the summits to the valleys – huge amounts of snow fell onto the transformed snowpack and led to high avalanche activity.”

Matthias WALCHER

Between the 19th and 25th of December, heavy snowfall finally arrived, its apogee around Christmas. The succeeding holidays were wintery in many parts of Tirol: snow from summit to valley floor, in many places there was enough snow for tours and variation skiing for the first time in the season. On top of that, brilliant sunshine radiated from a azure blue sky.

The shadow side of this idyllic picture lay hidden inside the snowpack: due to the delayed launch of winter and repeated rainfall up to high altitudes, particularly on 16 December, it happened that the snow cover in all aspects was expansively metamorphosed, manifesting a number of potential persistent weak layers (faceted crystals, surface hoar, rotten snow).

Due to the somewhat thicker snowpack in the northern regions, the layering at the snow base was more favorable. South of the Inn – from the Ötztal Alps to the Tux and Zillertal Alps – on the other hand, the snowpack layering was far worse. As of the snowfall around Christmas, accompanied by winds, a bonded slab which could easily be triggered was generated widespread atop the already present weak layer.

For the first time in the season, avalanche danger level “High” (4) was assigned. On 25 and 26 December, the first avalanche cycle started in which 14 avalanches triggered by persons were reported. During this time there was also a fatal avalanche incident on the Rosskopf in the eastern Tux Alps.

End of January: dangerous situation prone to accidents

Following a long dry period of fine weather and very little precipitation, on 27 January another conspicuous burst of winter was observed. A SW front brought large amounts of fresh fallen snow. Both fresh snow and drifts were deposited onto a weak old snowpack, particularly on west-facing, north-facing and east-facing slopes.

Particularly in the areas near the timberline at 1800-2200m, the snowpack surface was faceted and relatively evenly distributed. In places there were thin crusts up to nearly 2400m, in which faceted crystals had formed. Especially at this altitude and aspect, weak layers were often far-reaching.

On the morning of 28 January there was rainfall, initially up to about 1500-2200m widespread, accompanied by strong to storm-velocity SW winds. During the course of the day, the snowfall level descended, mostly to about 1000m, sometimes lower, depending on precipitation intensity. All in all in the western regions, along the Main Alpine Ridge and in East Tirol, 30-50cm of snowfall, locally up to 70cm, was registered.

The combination of heavy snowfall, strong winds and initially warm temperatures led to good bonding of the formed slab. This lay deposited atop persistent weak layers, creating a classic problem. As early as afternoon on 28 January, danger level “High” (4) was announced.

Naturally triggered avalanche activity reached its apex between late morning and late afternoon on 28 January. In this period, record-breaking values in 6-hr precipitation intensity were reached for this half of winter (November-April). This quite abrupt additional burden from fresh snow and drifts exceeded the limits of the weak layers and led to numerous naturally triggered avalanches. Many medium-sized, and more than a few large-sized slab avalanches were registered. During these hours there was an avalanche incident near the construction site for the new Längental power station in Kühtai: near the Zwölferkogel on a NW-facing slope at about 2500m, a loose-snow or slab avalanche triggered naturally and struck a vehicle at the construction site. The persons inside were slightly injured, the vehicle was totally destroyed.

Towards the end of the precipitation, winds slackened off significantly and temperatures dropped. Thus, on the surface there was often powder snow, making recognition of avalanche prone locations difficult for winter sports enthusiasts. Apart from alarm signals such as glide cracks, settling noises or observed fresh avalanches, there were often no clues of the danger.

On 29 January, a total of 14 avalanches involving persons were reported. The situation improved only gradually, not until 30 January was the danger level lowered to “Considerable” (3).

February to mid-March: largely favorable conditions

“The persistent low snow depths created a winterlong danger of injuries from rocks. It was an ongoing theme.”

Christoph MITTERER

Following the snowfall at the end of January and the resulting brief rise in avalanche danger (one of the few phases with danger level “High” – 4 this winter), generally favorable conditions set in. From 3 February until 13 March, more than five weeks, only danger levels “Low” (1) and “Moderate” (2) were announced, an unusually stable phase in high winter. At the end of February, in addition, temperatures above 0°C at altitudes above 3000m were recorded.

Mid-March: a skipped danger level “High” (4) during precipitation

Danger level “High” (4) was assigned on only 5 days in parts of Tirol in winter 2024/25. A further critical phase of intense avalanche activity was incorrectly recorded – it was particularly difficult to assess due to snowfall levels at extremely high altitudes..

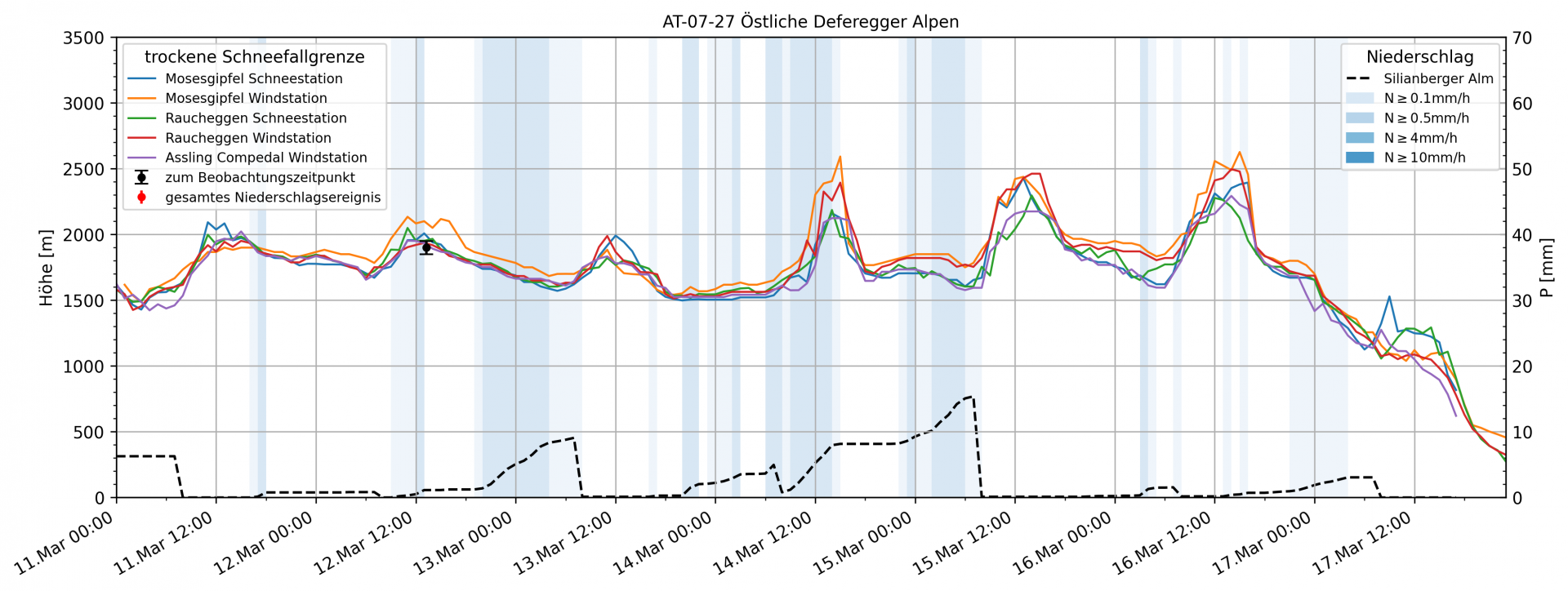

From 12-16 March a front system over Italy brought sizeable amounts of precipitation (40-70mm), especially south of the Main Alpine Ridge. Winds were generally weak to moderate-strength. What was striking: starkly fluctuating snowfall levels, far from those forecasted. For example, in East Tirol a snowfall level at 1000-1300m was forecast. But the measured data showed a different picture: rainfall up to about 2500m, no less than 800 metres of altitude higher than what was forecast as the zero-degree level. This observation was corroborated by observers in open terrain.

The warmth that seeped into the snow cover during this period favored the formation of slabs which were deposited on shady slopes atop a weak, faceted old snowpack surface. This resulted in high activity of naturally triggered slab avalanches, also reaching Magnitude 3 (large avalanche). The apex of this avalanche activity occurred in East Tirol on the afternoon of 15-16 March, as we learned from numerous reports from our observers. On Saturday, 15 March, a total of 7 avalanches involving persons were reported. In the subsequent analysis, it turned out that this was one of the most active avalanche periods of the entire winter.

“Only on very few days did danger level 4 prevail – large areas of avalanche prone locations announced to have high danger are the exception. An incorrect assessment, and thus, a missed time of high avalanche danger, occurred in mid-March due to the unexpectedly high snowfall level.”

Norbert LANZANASTO

Not until the end of the precipitation and drier air masses did the overall measure of avalanche activity during the phases of marked warmth become evident. Numerous naturally triggered slab avalanches occurred, particularly on very steep shady slopes at 2200-2500m. The announced danger level during this period was “Considerable” (3), which later proved to have been too low, it should have been assigned danger level “High” (4). The unexpectedly high snowfall level, at some junctures rising up to about 2500m, was the central factor for the wrong assessment.

Due to the marked formation of slabs and resultant numerous avalanche releases, even during this event many steep slopes unloaded their snow masses, thereby improving the safety situation for winter sports enthusiasts.

Overall, the enduring persistent weak layer problem in East Tirol could be characterized by the reactive phrase: “low probability – high consequences”. Danger zones for avalanches occurred rather seldom, but when an avalanche was provoked, large-sized slab avalanches were often unleashed. The avalanche prone locations were located mostly on steep shady slopes above 2200m and were difficult to recognize even for experienced mountaineers, since the snow blanketing the snowpack felt stable and hardened deeper down. A defensive, quite prudent selection of the terrain for a tour was the only reliable strategy for reducing risks.

End of March: fresh snow raises dangers again

Following the phase of marked avalanche activity in mid-March in East Tirol, there was another heightening of avalanche danger on 31 March: heavy snowfall and storm-strength NW winds led in eastern regions of North Tirol, and particularly in the eastern sector of the Main Alpine Ridge, to renewed danger level 4: “High.”

Just as in the earlier situations of marked danger over the course of the winter, weak layering near ground level was the major cause.

In addition, inside the masses of fresh snow and freshly generated snowdrift accumulations there were marked accumulations of graupel from region to region, creating an extremely reactive weak layer locally for a brief spell. Since during this phase an intermediate high-pressure front got mixed into the composition, there was often a thin melt-freeze crust that formed on the surface which tended to preserve the near-surface graupel, thereby making its dangerous potential last a little longer.

On sunny slopes in high alpine regions there also formed a weak layer of faceted crystals, supported by the swift drop in temperatures while the front moved through, leading to the danger pattern known as “cold on warm.”

This complex stage set for several reactive weak layers ultimately led to heightened naturally triggered avalanche activity during the period itself, as well as slow-motion improvement over the following days, including occasional person-unleashed triggerings, as is usual with the persistent weak layer problem. On 30 March, 11 avalanches involving persons were reported. In the days following, the number of reported avalanches involving persons decreased. From 1 to 3 April, a total of 7 avalanches were reported.

At lower altitudes the fresh snow was often deposited on bare ground. Heightened gliding snow was the result.

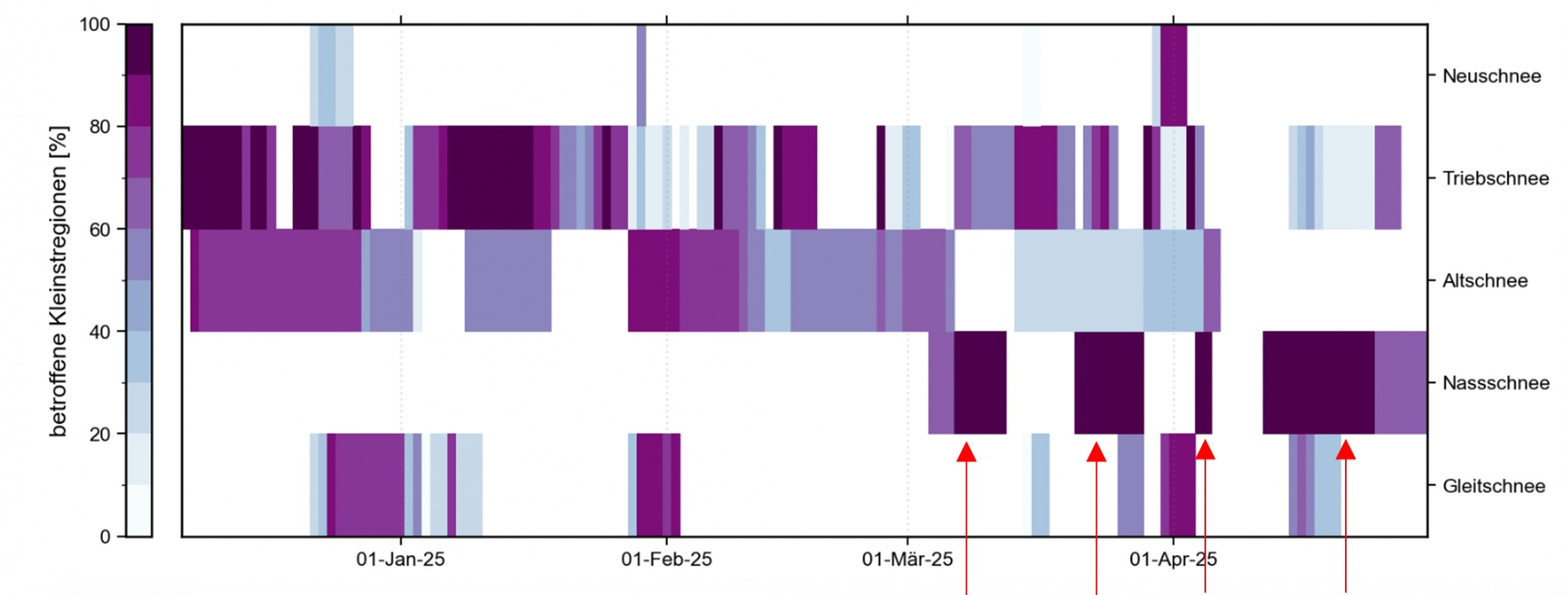

Wet-snow cycles

During the winter season 2024/25 there were several wet-snow cycles which left their mark, particularly in late winter. All five cycles occurred starting in March, the first of them right at the beginning of March. Between the second cycle in mid-March and the third cycle at the start of April, there was a short period of snowfall. The fourth cycle set in before Easter in mid-April and lasted until the beginning of May. The last cycle, which led for the first time to a completely wet snowpack in all aspects, began at the start of June.

04.-12. March 2025: “The First”

From 4-9 March, high-pressure weather conditions prevailed, with dry air and lots of sunshine. Solar radiation, aspect and steepness gradient of slopes were the major factors controlling the tempo of slopes becoming bare of snow. On sunny slopes, the likelihood of mostly small, wet, loose-snow avalanches triggering increased during the course of the day, particularly on south-facing slopes (SE-S-SW), where the snowpack was already isotherm. On steep south-facing slopes, snowmelt was far advanced, rendering danger zones rare. At the same time, there was heightened gliding snow activity on smooth ground due to increased water seepage into the snow.

A striking weather change on 10 March brought rainfall up to just below 2000m. The thoroughly wet snowpack which resulted led to loss of firmness inside the snow cover, and increasingly frequent loose-snow avalanches, often triggered by winter sports enthusiasts, and heightened gliding snow.

18.03. – 29. March 2025: “The Second”

As of 18 March, mild temperatures and intensive solar radiation led to the snowpack becoming increasingly wet. A high-pressure front over Central Europe brought beautiful weather and a zero-degree level above 3000m, causing the snowpack to lose firmness to a significant degree. The upshot: frequent wet loose-snow and glide-snow avalanches.

Starting on 21 March, southerly foehn wind, low-pressure front weather conditions and heavy cloud cover all generated diffuse radiation, thereby inhibiting nocturnal cooling. As of 23 March, a phase of precipitation followed, bringing warm/moist air, showers and enduring diffuse radiation – classic “laundry room weather.” Until 27 March the snow cover in all aspects below about 2200m was thoroughly wet (isotherm). A brief intermediate high brought temperatures rising again before a northern barrier-cloud front brought colder air masses and snowfall on 29 March.

03.– 05. April 2025: “The Third”

Following a brief spell of fresh snowfall, sunny spring weather again prevailed starting on 3 April 2025. The snow cover settled, clear nocturnal skies made good nighttime outgoing radiation possible. During the day. the melt-freeze crust softened increasingly, leading to the snowpack to become thoroughly wet and forfeiting firmness. The likelihood of wet-snow avalanches triggering rose particularly on steep south-facing and west-facing slopes. This phase of persistently high temperatures marked a third, although short-lived, wet-snow cycle which lasted until 5 April 2025.

Starting on 12. April 2025: “The Fourth”

A stable high-pressure front reinforced the wettening of the snowpack. In spite of clear nighttime skies and often good outgoing radiation, the high temperatures brought about a loss of firmness. Leaving early on tours was decisive, since even tiny weather changes, so typical of springtime, had an inordinate effect on avalanche danger.

Starting on 13 April, mild and moist air masses and foehn wind led to highly changeable “laundry room weather.” Local showers accelerated the wettening process. As a result, numerous wet loose-snow avalanches unleashed, most of them on west, north and east-facing slopes up to about 2400m, particularly south of the Inn.

A low-pressure front over Genua brought intensive precipitation starting on 16 April, in some places with rainfall up to over 2800m.

The combination of energy seepage through rain, diffuse radiation and high air moisture led to the snowpack becoming even wetter, including in steep terrain on shady slopes. Wet slab and glide-snow avalanches increased in frequency. A completely wet snowpack in all aspects prevailed up to at least 2200m. The wet-snow problem persisted until after Easter, amidst enduringly mild, changeable weather conditions.

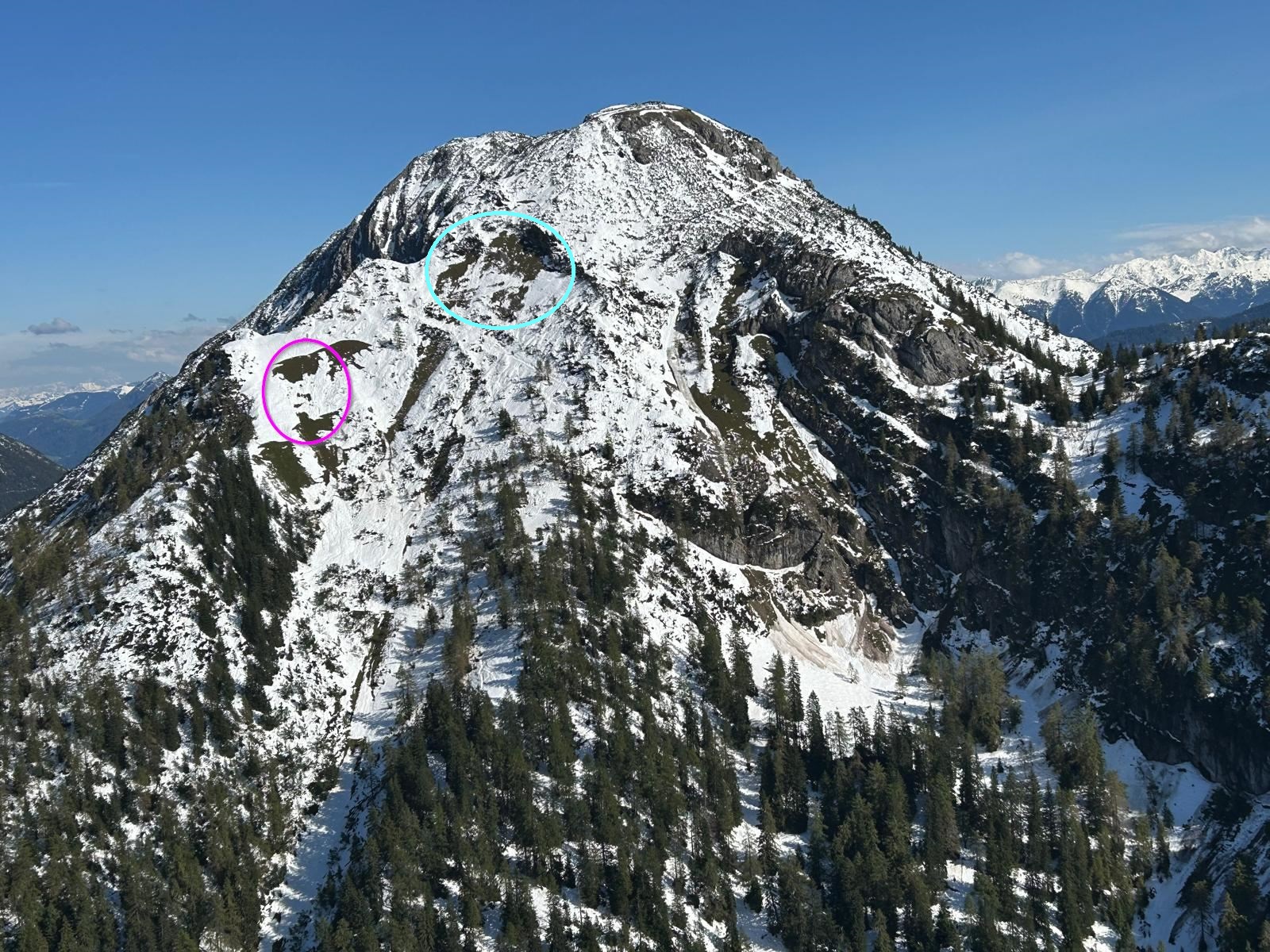

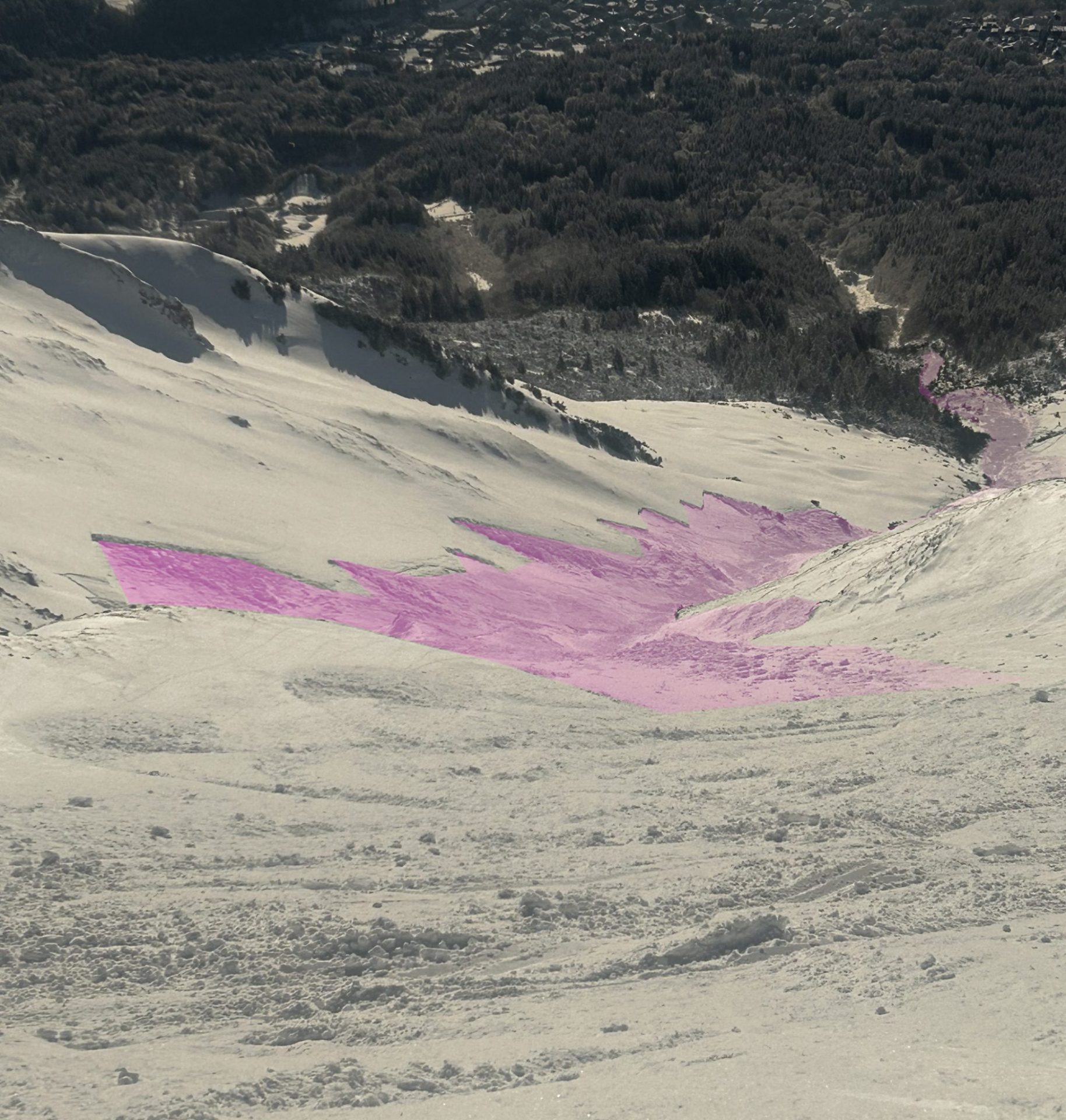

Start of June: large, in isolated cases very large slab avalanches

Following a generally cool and wet month of May, air temperatures rose in high alpine regions to slightly over 0°C during the daytime hours in the first week of June. Starting on Sunday, 9 June, temperatures surged. Thereby, the snowpack on north-facing slopes in high alpine regions was thoroughly wet down to the ground for the first time and the faceted, expansively metamorphosed weak layer from early winter weakened. This then led to isolated very large-sized naturally-triggered slab avalanche releases.